- Admission

- Discover Episcopal

- Our Program

- Athletics

- Arts

- Spirituality

- Student Life

- Support Episcopal

- Alumni

- Parent Support

- Knightly News

- Contact Us

- Calendar

- School Store

- Lunch Menu

« Back

Women’s History Month: Learning from the Past and Inspiring the Future

March 21st, 2024

Barbara McClintock. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

I was watching the movie “Legally Blonde,” the scene when Elle Woods is speaking with Warner, the man she followed to Harvard Law School, in the hall outside of class. She’s telling him about how busy she is and imagines she’ll be even busier the following year when she gets a spot in the prestigious internship everyone is vying for. Warner replies that Elle will never get the grades to qualify for that internship. “You’re not smart enough, sweetie.” Elle responds incredulously, pointing out that they got into the same law school, took the same LSATs, and are taking the same classes1. How is she not smart enough? I was surprised at my visceral reaction to this scene, and I hit pause. Though most of my classmates in graduate school were collaborative and encouraging, a few male classmates were anything but. I remembered my anger and frustration, thinking the same things Elle said when those classmates would casually dismiss their female classmates' ideas and contributions. Didn’t we get into the same grad school, take the same GRE, and attend the same classes?

Before entering K-12 education, I was a grad student focused on research in the biological sciences. Though considered one of the more gender-balanced scientific fields, this was still male-dominated. After I graduated with my PhD, published reports found that about half of biology graduate students were women, and about 40% of postdoctoral researchers were female. However, only 36% of assistant and 18% of full professors were women2. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that high-achieving male faculty trained 10-40% fewer women in their laboratories compared to the number of women trained by other investigators, a potential explanation for the gender imbalance in tenured professor positions3. And this reality certainly shaped my experience.

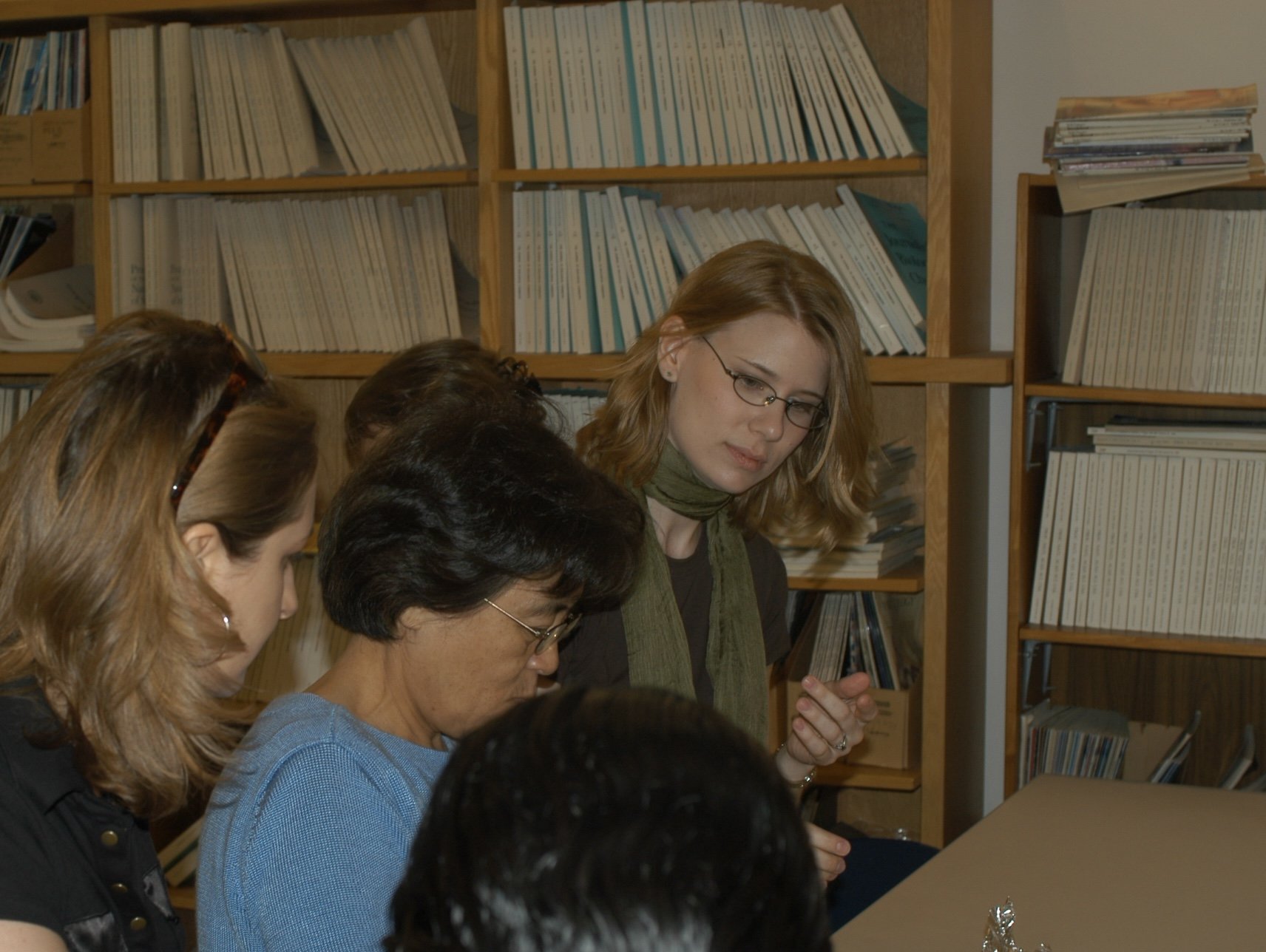

So, when a group of Episcopal Middle School students asked to interview me for a video in honor of Women’s History Month, I struggled with one of their questions: “Who are the influential women in your life?” I grew up in a family of strong women, like my mother, but I wanted desperately to tell these girls about a female STEM mentor, someone who was my guide through college or graduate school. I really couldn’t. There were female professors in my department, strong women I admired, who taught my classes and interacted with me occasionally, but there were not many, so most of those professors with whom I connected and worked day in and day out were men. I had incredibly supportive, wonderful mentors, including my PhD advisor, but they weren’t female. Our journeys were different in many ways.

Instead, my female STEM idols came from reading history. An icon in the field of genetics, Barbara McClintock studied genetic mechanisms in maize plants from the 1930s through the 1960s. Her work led to the discovery of control elements for gene regulation as well as transposable elements, genetic sequences that can “jump” from spot to spot on chromosomes, changing position and disrupting the function of other genes. Her work was beautiful and elegant. Though widely respected as a researcher, her conclusions were so at odds with the commonly held ideas about heredity that transposable elements were not widely accepted until other researchers “rediscovered” these very same mechanisms in different organisms4,5. Dr. McClintock won numerous awards for her scientific contributions, including the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983. She was the first woman to win an unshared Nobel Prize in that category6,7.

To me and many women in science, Barbara McClintock is like a superhero, but better - what she achieved was through hard work and study. Because of her fame, I learned more about her journey and life than the few female professors I encountered. This opportunity to learn about women like Dr. McClintock is the value, I think, of Women’s History Month. Highlighting such stories allows young girls and women to see those who succeeded before them, even in fields that don’t always feel welcoming to them. These stories enable young women to picture themselves succeeding and consider what is possible.

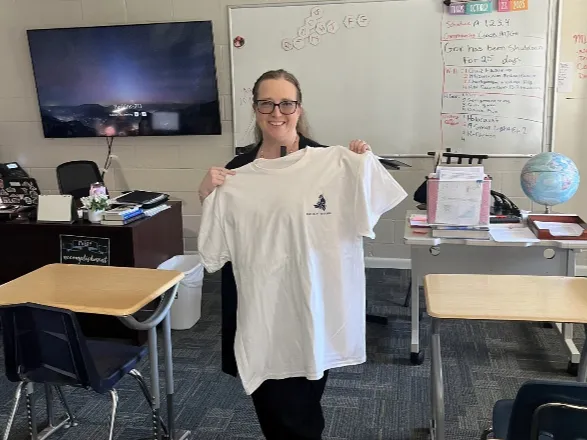

Now, I work in K-12 education, and I am blessed to be surrounded by strong women: women who have been successful in leadership, business, science, math, law, the arts, and so many other fields; women who have chosen to use their talents and experiences to help the next generation of students learn, thrive, and succeed; women who share their stories and experiences with their students during Women’s History Month and every month.

Sources:

1 Luketic, Robert. Legally Blonde. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Distributing Corporation (MGM), 2001.

2 Trafton, Anne. "Research Reveals a Gender Gap in the Nation's Biology Labs."

MIT News [Cambridge, MA], 30 June 2014, Accessed 13 Mar. 2024.

3 Sheltzer, Jason M., and Joan C. Smith. "Elite Male Faculty in the Life Sciences Employ Fewer Women." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 111, no. 28, 30 June 2014, pp. 10107-12. Accessed 13 Mar. 2024.

4 National Academy of Sciences. 1995. Biographical Memoirs: Volume 68. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

5 "Barbara McClintock." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Feb. 2024. Accessed 13 Mar. 2024.

6 Barbara McClintock – Biographical. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2024. Wed. 13 Mar 2024.

7 "Barbara McClintock: The Barbara McClintock Papers." NIH National Library of Medicine Profiles in Science. Accessed 13 Mar. 2024.

Dr. Sara Fenske pursued a career in education because of her love of science and desire to share that passion with others. Knowing the impact a great education can have, Sara chose to focus on teaching and curriculum design, with a focus on continuous improvement. Dr. Fenske joined Episcopal as a member of the science faculty and the Academic Programs Special Projects Manager. In 2018 she transitioned into the role of Dean of Academics. In this new position, Dr. Fenske works collaboratively with the Head of School, division heads, department chairs and faculty members to ensure Episcopal’s continued strong and relevant academic performance. Prior to joining Episcopal, she was the Science Department Chair and taught at Linden Hall in Pennsylvania. She has a Bachelor of Science in cell and molecular biology from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a PhD in biology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Episcopal School of Baton Rouge 2025-2026 application is now available! For more information on the application process, to schedule a tour, or learn more about the private school, contact us at [email protected] or 225-755-2685.

Posted in the categories All, The Teachers' Lounge.

Other articles to consider

Dec12From Service to Song: Lower School Students Celebrate Christmas in Two Languages

Dec12From Service to Song: Lower School Students Celebrate Christmas in Two LanguagesEpiscopal third graders celebrated the season and French heritage with a special holiday program in the Lewis Family Memorial Chapel of the Good Shepherd.

See Details Dec11Upper School Recognizes Excellent Educators

Dec11Upper School Recognizes Excellent EducatorsThis semester, Upper School students recognized teachers who inspire, support and challenge them every day. Congratulations to our Excellent Educator honorees.

See Details Dec11Smashing Goals, Building Community: Episcopal’s Shepherd’s Market Food Drive Success

Dec11Smashing Goals, Building Community: Episcopal’s Shepherd’s Market Food Drive SuccessThe Episcopal Shepherd’s Market Food Pantry “Great Turkey Giveaway” food drive broke records. We’re proud of our students and families for building community through service.

See Details Dec4Sixth Grade Care Packages Build Community and Bridge Generations

Dec4Sixth Grade Care Packages Build Community and Bridge GenerationsEpiscopal sixth graders shared holiday cheer by sending care packages to members of the Class of 2025. A tradition that proves once a Knight, always a Knight! Plus, learn more about upcoming alumni holiday events.

See Details

Categories

- All

- Admission

- Athletics

- College Bound 2019

- College Bound 2020

- College Bound 2021

- College Bound 2022

- College Bound 2023

- College Bound 2024

- College Bound 2025

- Counselors Corner

- Episcopal Alumni

- Giving

- Head Of School

- Lower School

- Middle School

- Spirituality And Service

- Student Work

- The Teachers' Lounge

- Upper School

- Visual And Performing Arts

Recent Articles

- 12/12/25From Service to Song: Lower School Students Celebrate Christmas in Two Languages

- 12/11/25Upper School Recognizes Excellent Educators

- 12/11/25Smashing Goals, Building Community: Episcopal’s Shepherd’s Market Food Drive Success

- 12/4/25Sixth Grade Care Packages Build Community and Bridge Generations

- 12/3/25What is Project Based Learning?

- 12/2/25Celebrating the Season with Student Art

- 12/2/25Christmas Through a Child’s Eyes by Jenny Heroman Koenig '01